selected past works

Tongue-tied (2000)

Tongue-tied (2000), is a bronze life-cast sculpture of two cow tongues twisted together. This work presents a compelling visual metaphor for the inability to speak. It suggests dual conditions: enforced silence and self-imposed muteness due to fear of retribution. As Streak articulates, “Tongue-tied is a visual expression of the inability to speak. It posits two simultaneous positions: voices silenced and disallowed to communicate and a self-imposed silence for fear of retribution.”

This concept parallels Martin Niemöller’s reflection on the consequences of inaction:

“First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.”

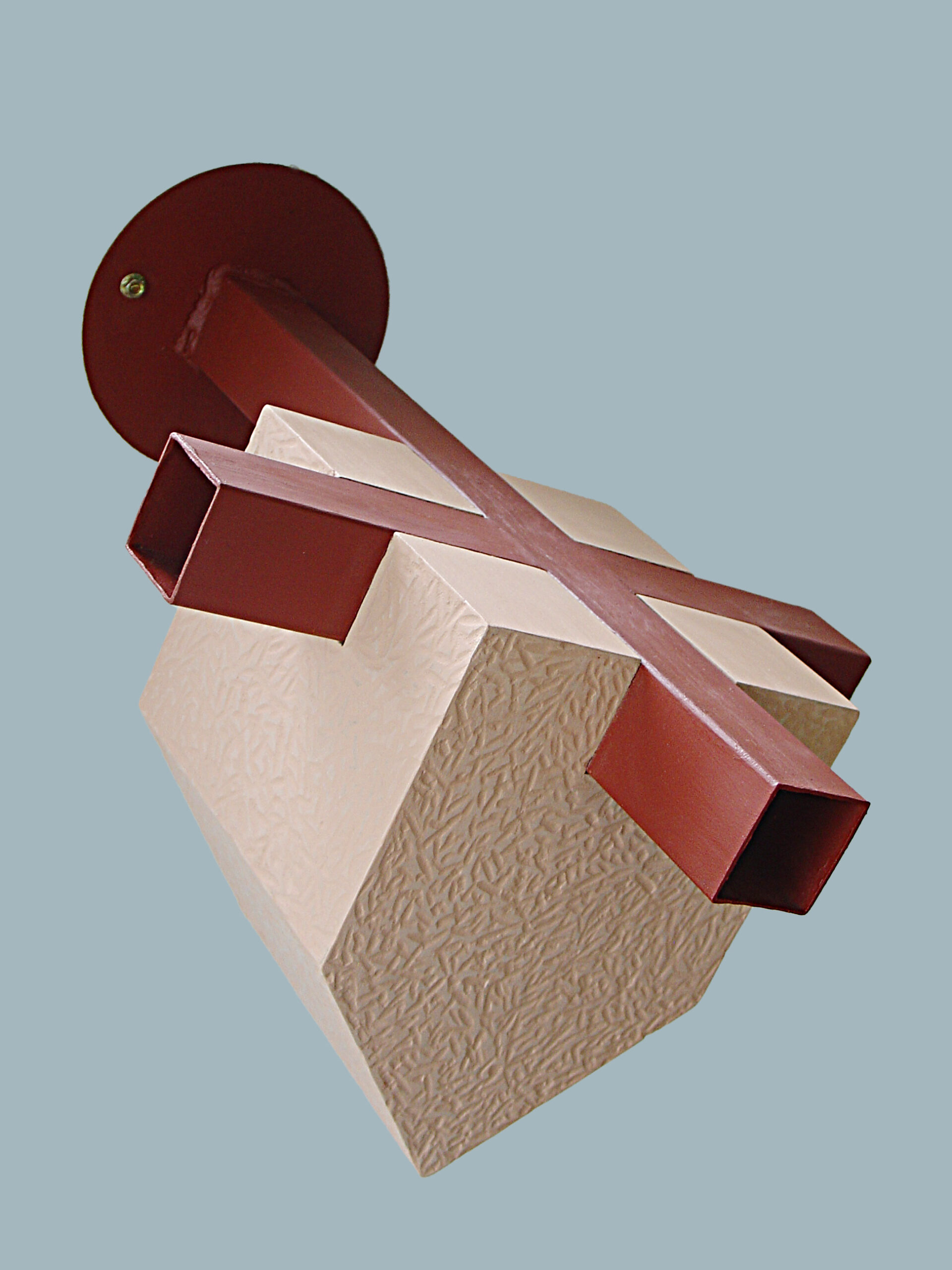

Home (2004)

Home (2004)

Mild steel, MDF, paint. 500 mm x 350 mm x 350mm

Home (2004) is a conceptual sculpture that serves as a parodic response to Bruce Nauman’s The Center of the Universe (1988). Nauman’s commissioned work, a concrete structure with tunnels extending towards the cardinal directions and an opening to the sky at the centre, symbolises the cosmological notion that the universe expands uniformly in all directions. This principle implies that any point can be considered the centre of the universe, encapsulating a paradoxical sense of universality and centrality.

In contrast, Home (2004) distills this idea into a solid MDF block, emulating the archetypal shape of a house. It is bisected by a 50mm mild steel square tube, echoing Nauman’s cardinal tunnels. This structural element serves both as a physical reference to Nauman’s work and as a metaphorical commentary on the concept of ‘home’ as a central, yet ambiguous, notion in human experience.

“The concept of home is also a constitutive metaphor in much political debate, and has been instrumental in the shaping of the public–private distinction” (Davies 2014: 153). By juxtaposing the familiar image of a house with the abstract idea of cosmic centrality, Home (2004) explores the tension between private sanctuaries and universal principles, inviting viewers to reflect on the fluid boundaries between personal space and broader existential or political frameworks.

Alexandria (2005)

Bronze, life-cast, one-of. Produced for the exhibition titled – Twist in the Tale – curated by Virginia Mackenny for the Klein Karoo Kunstfestival (KKNK), 2005.

Alexandria is a feminine form of Alexander originating from Greece, meaning “defender of humankind” or “defender of the people.” Female sacrifice matters too.

Collection: Sasol Art Collection

The Apartment (2007)

“Greg Streak is an interdisciplinary practitioner working in sculpture, video, installation and documentary filmmaking. His work is characterised by formalistic concerns and a preoccupation with the materiality of substance and things, but also space, both physical and psychological”. – Dr Kathryn Smith

In 2007, I was awarded the Ampersand Fellowship – a three month residency in an apartment in TriBeCa, New York City with no expectations other than to assimilate and contemplate for future creative ventures.

The Apartment (2007) is a minimalist architectural sculpture crafted from balsa plywood, embodying a duality that speaks to both retreat and homage. On one hand, it offers a respite from the imposing jungle of urban monoliths made of glass, concrete, and steel, creating an intimate internal space. On the other hand, it pays tribute to these very structures, mimicking their stern, impenetrable facades. This duality reflects the intertwined nature of physical and psychological spaces, where the internal sanctuary contrasts sharply with the external coldness, evoking both solace and isolation.

Collection: Ampersand Foundation

Some Things Are Better Left Unsaid (2008)

“Greg Streak’s piece, Some Things Are Better Left Unsaid (2008),consists of a cross constructed out of energy saving light bulbs. The cross correlates perfectly to an actual statue of Christ on the cross on the other side of the road, on the grounds of a Catholic Church. While the gallery is accessible to the public, the church is less so, surrounded by security fencing”.(Machen 2008: n.p.)

Marquette for Mapping a Dyslexic Heart (2009). Lead, cotton thread, stainless steel pins, steel-wire cable. 500mm x 300mm x 30mm.

In a peregrination between process, material and ideas, one of the strongest works on exhibition is Greg Streak’s Marquette for Mapping a Dyslexic Heart. Masterfully evocative, this conceptual rendering of emotional dysfunction a result of ‘the inability to place oneself – both physically and emotionally’ is conveyed as a corrugated lead plateau pitted by undulations, pins and attached embroidery cotton. Here material deployed reminds of the tenacity of the ordering impulse of the mind (pins, thread, undulations) despite the overwhelming weight of a dysfunctional (dyslexic) reality (lead). Originating in, while at the same imploding notions of assumed and perhaps even desirable order, Streak simultaneously de- and reconstructs a sense of cohesion and direction associated with lived experience, instead plotting a terrain marked by chaos, disconnectedness, the unpredictable and the illogical. – Professor Juliette Leeb-du Toit

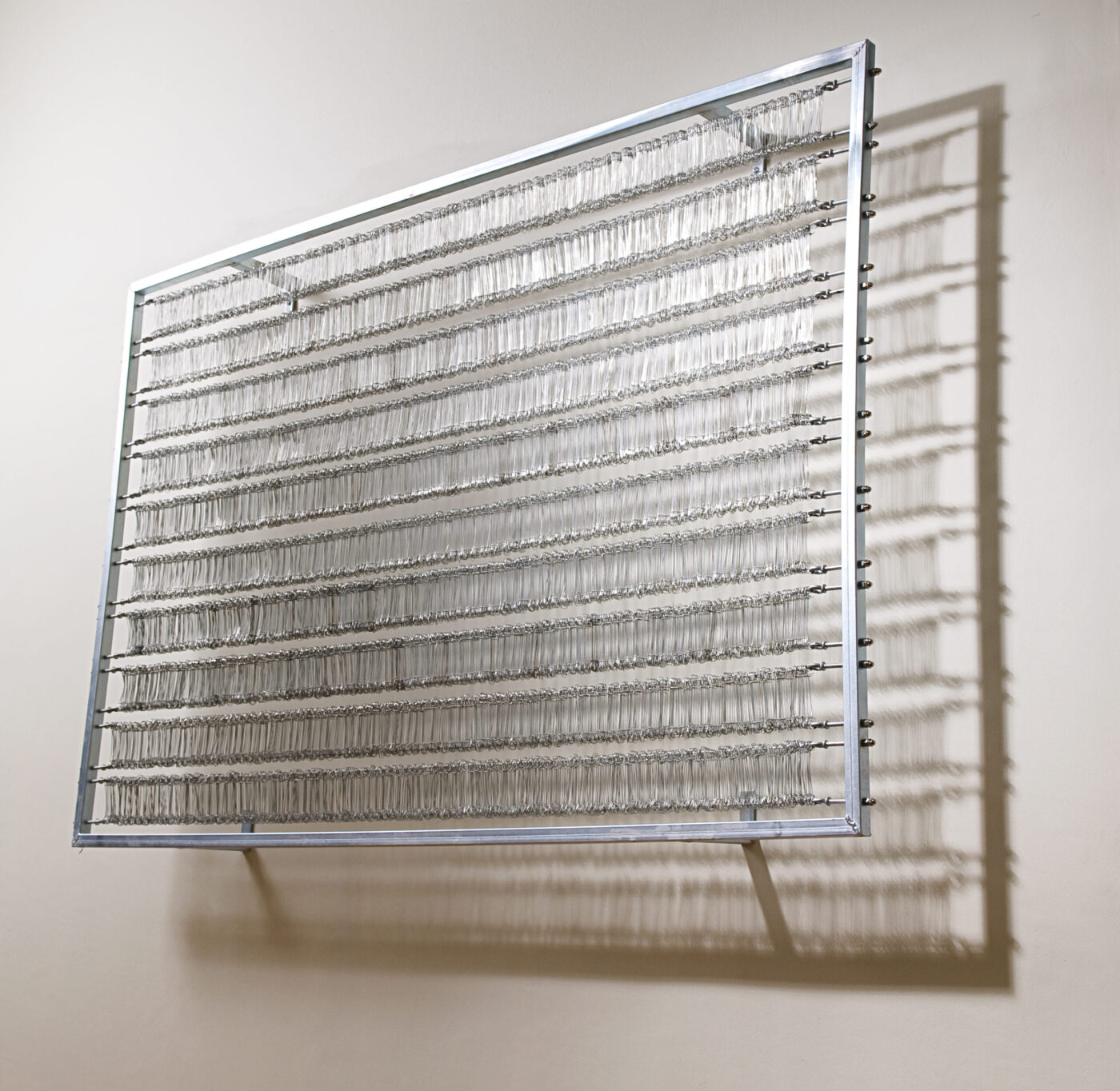

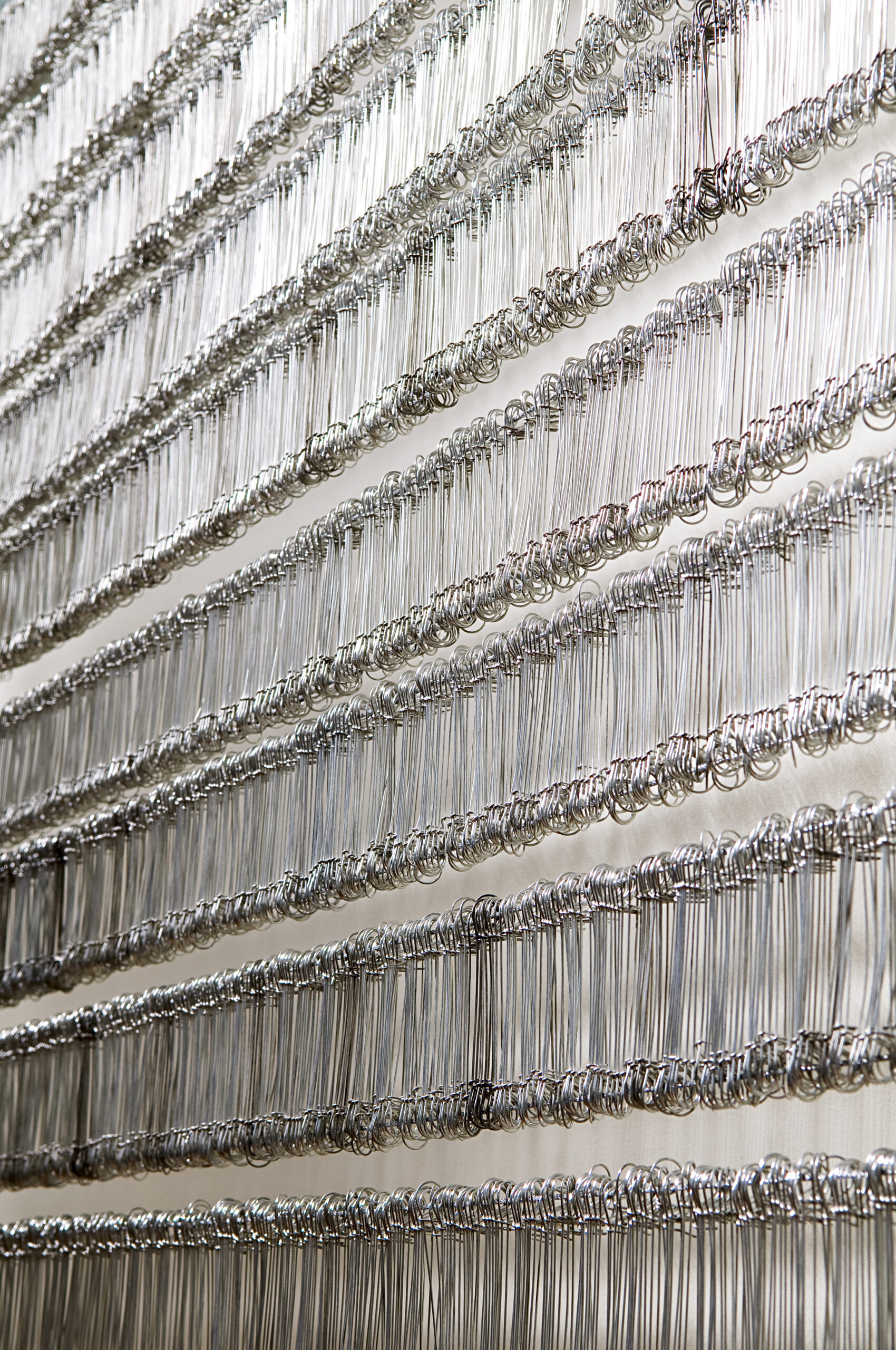

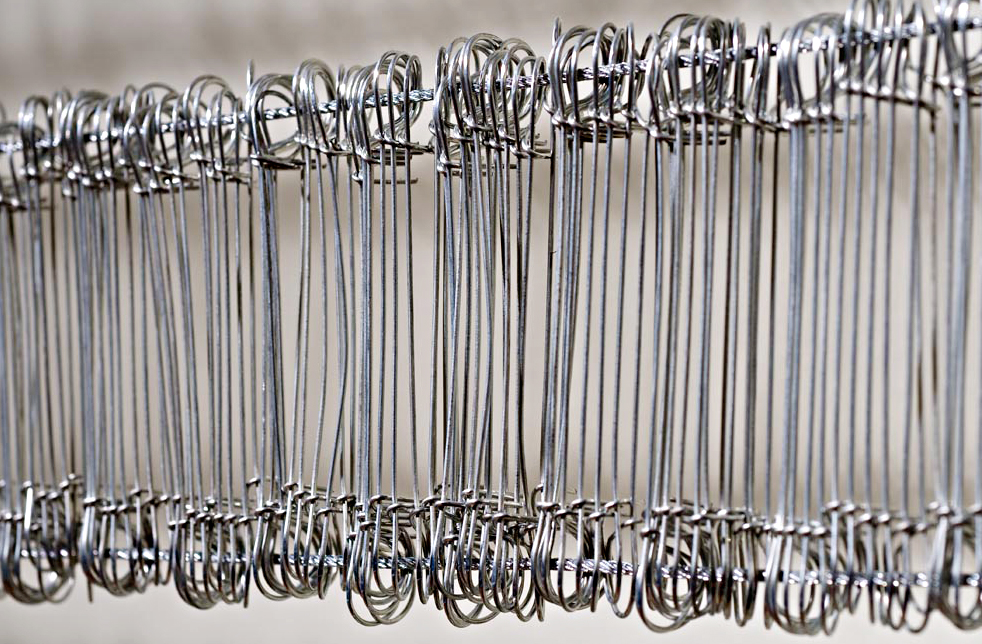

Abacus for Longing (2009). Mild steel tube, wire ties, steel wire cable, eye hooks. 1800 x 1150 x 180 mm.

Abacus for Longing (2009) serves as a poignant metaphor for absence and longing. This conceptual work comprises approximately 10,000 wire ties, each meticulously held in place by wire gyres. The sheer abundance of these wire markers, paradoxically, signifies an emotional vacuum. Each tie, akin to the scratches on a prison wall, represents an attempt to register and record loss. The dense accumulation of ties becomes a visual and tactile representation of yearning, where the repetition and multiplicity of elements underscore the depth and persistence of emotional absence. Through this use of everyday materials, Abacus for Longing transforms the act of marking time and memory into a powerful commentary on the human experience of longing and the seemingly futile attempts to quantify and document the intangible.

Cradle to Hide from the World (1 of 2 parts) 2010

“Greg Streak’s piece, titled Cradle to Hide from the World (1 of 2 parts), is itself contained in the most constrained corner of the gallery: as such it offers an example of how curation affects the meaning of a work. If the piece – a powder-coated white metal cradle that is also reminiscent of a cage – had been hanging from the centre of the gallery, the effect – and meaning – would have been subtly but substantially different. Like much of Streak’s work, it is both beautiful and sinister, balancing the cold and hard with the warm and protective”. (Machen 2009: n.p.)

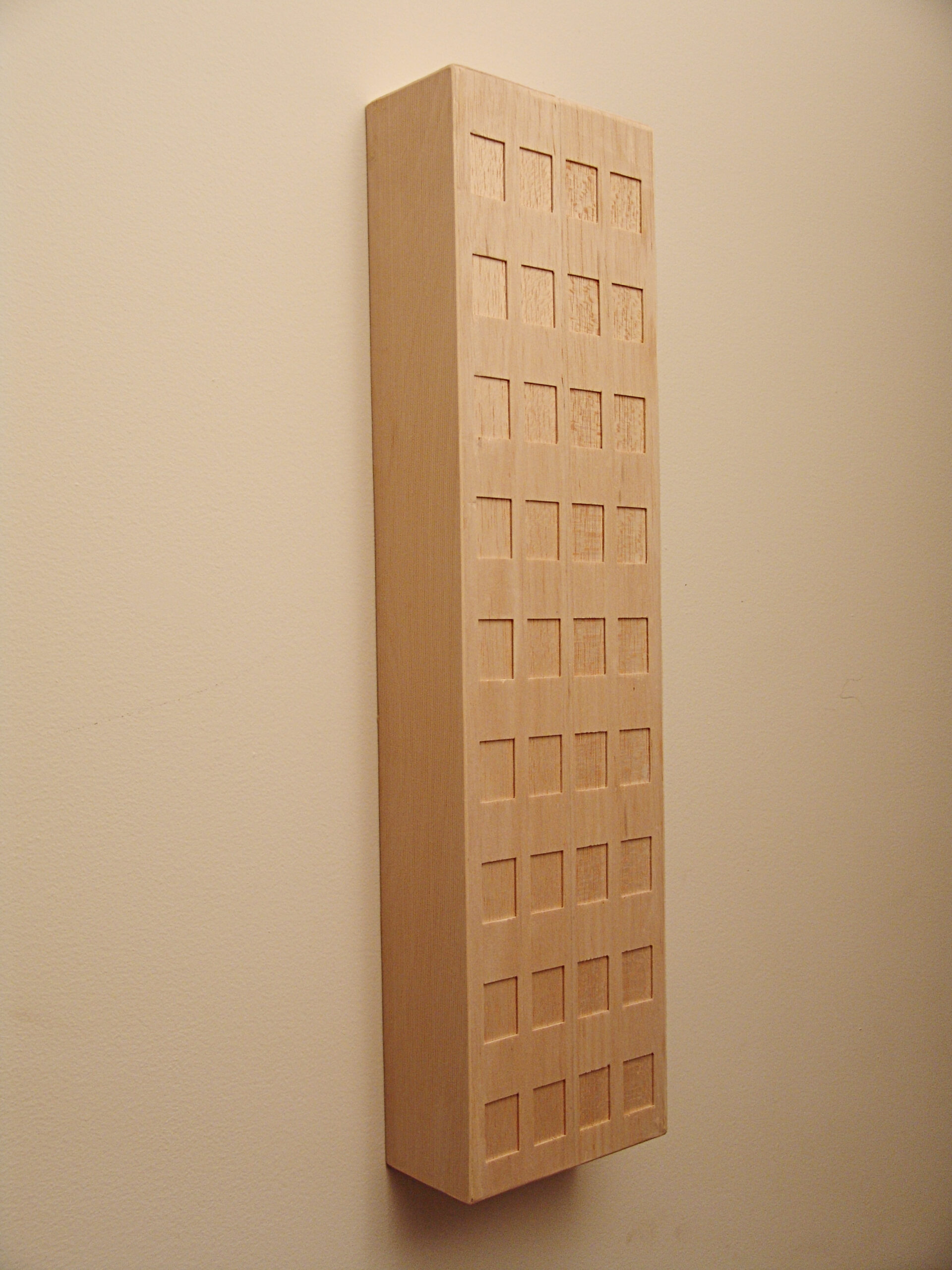

Flash Dreams (2014) , carved Jacaranda, 600mm x 150mm x 200mm.

Flash Dreams (2014) is a sculptural piece carved from Jacaranda wood. Inspired by the traditional Zulu headrest, which is designed to compress the pituitary gland at the back of the neck, it aims to induce a dream state and facilitate a connection to the ancestors. This ancient practice contrasts sharply with our contemporary obsession with technology, where we remain “plugged-in” even as we seek rest and disconnection.

Flash Dreams embodies a deliberate synthesis of the traditional and the technological. This ‘cyborg dream pillow’ merges the tactile, organic qualities of wood with the concept of modern connectivity, symbolizing a collision and cross-pollination of two distinct worlds. By juxtaposing these elements, the piece explores the convergence of ancestral spirituality with the pervasive influence of technology in our lives, inviting viewers to reflect on how these forces shape our experiences, even in sleep.

Title: Applying my Mind (2015) | carved Jacaranda wood | 800mm x 300mm x 350mm | Seventy eleventy six hundred thousand million and ten.

The sculpture, Applying my Mind (2015), depicts a headless figure dressed in a suit, identified as former South African President Jacob Zuma. This figure holds its own head in its hands, positioned in front of the groin area. The head is detailed, featuring recognisable facial characteristics and eyeglasses, making the depiction unmistakably Zuma. The sculpture’s title and exaggerated pricing mock Jacob Zuma’s numerical blunders and controversial public statements. The headless figure represents a disconnect between his actions and his public persona, with the placement of the head suggesting the perceived lack of direction and accountability during his presidency. The head’s positioning hints at the idea that Zuma’s decisions were influenced more by personal and instinctual motivations than by rational or ethical considerations. This placement critiques his perceived impulsiveness and indulgence in personal matters over public responsibilities.

In an exhibition setting, this work invites viewers to consider the complex interplay between personal life and public responsibility in political leadership. The humorous yet pointed representation of Zuma, combined with the head’s symbolic placement, effectively engages the audience, prompting reflection on the dynamics of power, accountability, and personal conduct in political figures.