Site-specific works

To rent: Remains of the cash cow (2013)

Project: KADS 2

Location: Zeilstraat, Amsterdam

Work: to rent: remains of the cash cow (2013)

KadS 2013 [KUNST AAN DE SCHINKEL/ART ALONG THE SCHINKEL] A cultural festival in Amsterdam

22 Sep – 17 Nov 2013

This autumn Soledad Senlle Art Foundation will be holding the second edition of the art festival KadS [KUNST AAN DE SCHINKEL] in Amsterdam South. Initiator Marisol Ferradás, working in close collaboration with the curator Christine van de Bergh, has selected ten national and international contemporary artists. The artists stemming from various disciplines will intervene in the public space and create site-specific work for the Schinkel neighbourhood.

With this festival Soledad Senlle Art Foundation reflects on the role of art in our society. The artistic interventions refer to current social developments and will offer the public a different view of daily reality. Unlike the first edition of KadS, where the beauty and history of this relatively unknown Amsterdam neighbourhood were given centre stage, the emphasis this year lies on the Schinkel neighbourhood’s busy and chaotic centre: Zeilstraat and Hoofddorpplein.

‘Lack of occupancy’ serves as the inspiration for the work of the South African artist Greg Streak. According to Streak the problem of unoccupied premises is a worldwide issue that is also evident in the Schinkel neighbourhood. His sculpture titled ‘To Rent: Remains of the Cash Cow’ is a 2 x life-size version of a cow’s head covered with 5-euro notes, which will be displayed in a vacant retail unit. Participating artists in KadS 2013 are: Jacqueline Dauriac (FR), Emilie Faïf (FR), Yasmijn Karhof (NL), Sachi Miyachi (JP), Marike Schuurman (NL), Sarah van Sonsbeeck (NL), Greg Streak (ZA) and the duo Thijs de Zeeuw and Pieter Alexander Lefebvre (NL).

Artists statement:

To rent: Remains of the Cash Cow (2013) is a provocative and ironic commentary on the economic crisis, encapsulating the absurdities of fluctuating monetary values and the art market’s peculiar dynamics. This work features a cow’s head, meticulously covered with real and printed €5 notes, highlighting the paradoxes surrounding the value of money. The €5 note, chosen for its history of easy forgery and subsequent redesign, serves as a critical symbol in this piece. Its inclusion questions the inherent worth of currency—pieces of colored paper that gain and lose value arbitrarily.

This artwork, priced in the commercial art market, deliberately subverts its own critique by entertaining the paradox of an artwork’s value within a capitalist framework, thus turning its gaze back on itself. The use of real currency, now rendered meaningless in this context, challenges viewers to reflect on the fluidity and constructed nature of economic worth.

The cow, a potent symbol in Dutch culture revered for its dairy-related significance, adds layers of cultural resonance to the piece. This isolated cow’s head draws a parallel to Damien Hirst’s – One Thousand Years – where a real cow’s head decays in a glass enclosure, swarmed by flies. While Hirst’s work revels in visceral realism, To rent: Remains of the Cash Cow shifts the focus to the notion of a “real economy” and the often arbitrary values assigned to money and art. Through this juxtaposition, the work opens a debate on what truly constitutes value—whether in economic or artistic terms—and how these values intersect and diverge in contemporary society.

Fake Empire (Blue Monday) (2011)

Project: Cop 17

Location: Sunken Garden Amphitheatre, Durban Beach Front

Work: Fake Empire (Blue Monday) 2011

Fake Empire (Blue Monday) was a temporary public artwork specially commisioned from Greg Streak by VANSA as part of the DAC’s contribution to the COP17 creative programme. A reflective and finely realised work, engaged with it’s physical surroundings and the wider implications of COP17.

Artists Statement:

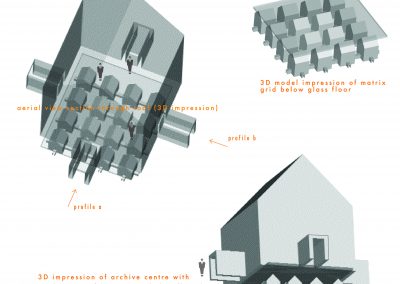

Fake Empire (Blue Monday) (2011) critically examines the conflict between capitalism and environmental sustainability through a striking visual and structural metaphor. The piece is anchored in the significant economic collapse of September 2008, a period that exposed the fragility and assumptions of the global economy. This tumultuous time, especially September 29th, known as “Blue Monday,” when the world’s economy dramatically plummeted, serves as the backdrop for the artwork’s narrative.

The structure of Fake Empire (Blue Monday) is based on the fluctuations of the Dow Jones Stock Exchange during this period, depicted in a graph that is then superimposed onto a cityscape silhouette. This cityscape, rendered in plywood and steel, mirrors the materials commonly used in urban construction, highlighting the physical and metaphorical frameworks of capitalist societies. The entire structure is inverted, symbolising a topsy-turvy world where traditional economic values are upended.

Emerging from this inverted cityscape are indigenous plants, rescued and revitalised by Clive Greenstone, who nurtured them in a “rooftop garden.” These orphaned plants, thriving despite their discarded origins, use the cityscape below as a symbolic compost. This inversion and growth from decay underscore a potent message: despite the artificial and often destructive nature of capitalist systems, life and nature persist, adapt, and reclaim.

The white plastic facades in the piece evoke an anaemic, sterile, and emotionless urban environment, in stark contrast to the vibrant and resilient plant life. A thin red line runs through the piece, tracing the cityscape from behind and echoing the original stock exchange graph, serving as a visual marker of economic fluctuations and their impacts on the built environment.

Fake Empire (Blue Monday) thus becomes a powerful commentary on the environmental toll of capitalism and the resilience of nature. By juxtaposing the sterile cityscape with thriving indigenous plants, the artwork suggests that true sustainability lies not in the relentless pursuit of economic growth but in harmony with the natural world. The inversion of the cityscape and the plants’ growth from it visually reinforce the idea that the remnants of our economic systems can, paradoxically, provide the foundation for renewal and ecological resilience.

Centre of the Universe (2008)

Project: Cascoland _2008

Place: Little Cato Manor, Durban, South Africa

Work: Centre of the Universe

What is Cascoland? http://cascoland.com

Public Art is an important tool in activating and developing public space. In the kind of Public Art Cascoland promotes, inter-disciplinary artists engage themselves in communities to collaborate with audiences and members of the communities in shaping their public space through dialogue and participation. The intention is to motivate and mobilize audiences to become an active participant in the process initiated by the artists and in which the eventual artwork is not as much a physical object but a change in perception of public space with the audience.

Centre of the Universe – 2008

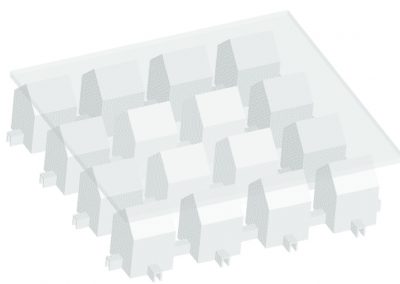

Centre of the Universe (2008) is a site-specific installation by Durban-based artist Greg Streak, created for Cascoland 2008. This project features three concentric octagonal formations, ingeniously constructed from interconnected plastic buckets, basins, white PVC pipes, and mild steel base plate connectors. This multi-layered amphitheatre reflects both practical ingenuity and cultural resonance, drawing on the versatile use of everyday objects and the deep-rooted tradition of oral storytelling in African communities.

Structural Description

The innermost octagon, forming the heart of the installation, consists of 8 brown/grey 5-litre plastic buckets, each supported by a nested pair and inverted to serve as individual seats. These are connected via white PVC pipes inserted into laser-cut mild steel tubes with base plates, creating a central void approximately 2 meters wide. This space is designed to accommodate performances or other communal activities.

Radiating outward from this core, the middle layer comprises larger green circular basins, joined at their rims and inverted to form slightly elevated seating. Extending from these are further PVC pipe connectors that link to the outermost structure, formed by large red oval basins, also inverted and stacked, allowing each to seat two people. Altogether, the installation provides seating for 32 individuals, encapsulated within the three octagonal layers.

Conceptual Outline

The installation’s form and function draw inspiration from two key concepts:

1. Tetrahedral Design: The notion of a tetrahedral structure, characterised by its four lateral planes and top and bottom surfaces, informs the geometric integrity of the installation. This concept underscores the modular and interconnected design, mirroring the complexity and adaptability of informal trading environments.

2. Amphitheatre: Serving as a modern reinterpretation of an ancient amphitheatre, Centre of the Universe creates a versatile space for public engagement, akin to traditional arenas used for performances, games, and storytelling. This design pays homage to the cultural heritage of oral storytelling, particularly within Zulu and other African tribal communities, where stories are shared around a fire in communal gatherings, preserving traditions and fostering community bonds.

Cultural Significance

Plastic basins, bowls, and buckets are ubiquitous in informal trading and daily life across South African cities. These vibrant, multipurpose containers are employed in diverse ways—from holding fruit in street markets to serving as makeshift washing basins in rural areas and cooling beverages in the absence of refrigeration. By incorporating these elements, Centre of the Universe acknowledges their proliferation and adaptability in marginalized urban and rural contexts, aligning with Cascoland’s focus on site-specific interventions along informal trading routes.

The installation’s title, Centre of the Universe, encapsulates a profound and democratic idea: the center of one’s universe is defined by one’s own experiences and community. For the residents of Cato Manor, where the installation has found a permanent home thanks to the efforts of Bronwyn Lace and Fiona Bell, this project symbolizes a central gathering place, a locus for communal interaction, and a space for cultural expression.

By referencing both the pragmatic and cultural uses of common objects and the historical imagery of amphitheatres, Centre of the Universe weaves together themes of community, resilience, and the reimagining of shared spaces. This installation not only serves as a functional arena for communal activities but also as a reflection on the value of collective experiences and the fluid, evolving nature of public spaces in shaping a community’s sense of place and belonging.

Composter (2004)

Peroject: Hiv(e)

Curator: Greg Streak / PULSE

Location: Gozololo – children’s centre – Kwa mashu, Durban, South Africa

Work: composter (2004)

Hiv(e) was the critically acclaimed project orchestrated by Greg Streak of PULSE. Artists were to respond to the functional needs of Gozololo (a centre for children with AIDS or orphaned as a result of their parents having died of the pandemic). The brief was to make a functional contribution whilst still retaining artistic integrity and poetry.

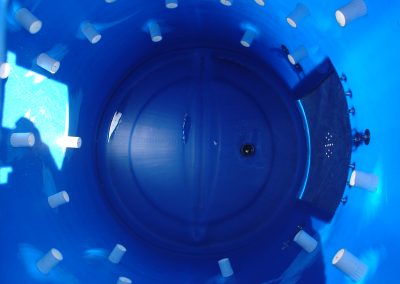

Composter (2004) is a sculptural and functional artwork created in response to the history and transformation of Gozololo, a care centre built on a former rubbish disposal site. Greg Streak, inspired by the metaphorical richness of this metamorphosis, conceived the piece to embody both the physical and symbolic processes of decay and renewal.

Gozololo’s past as a dumping ground for society’s throwaways juxtaposes starkly with its present role as a center of care and nurturing. This transformation from decay to vitality mirrors the natural process of composting, where organic waste decomposes and enriches the soil, fostering new growth. Drawing on this metaphor, Streak designed Composter (2004) to reflect the cycle of waste and regeneration, echoing the rebirth of the Gozololo site itself.

The artwork utilizes a plastic industrial drum, modified with a series of galvanized steel attachments that enhance its functionality as a composter. These attachments are meticulously mounted to the drum’s varying surfaces, facilitating the composting process. Streak reconfigured a section of the center’s perimeter fence to support and integrate the composter, positioning it so that the fence bisects the drum horizontally. This innovative design allows the composter to serve both the internal and external spaces of Gozololo.

Two access doors, positioned on either side of the fence, enable organic waste to be deposited into the composter from both inside the care center and the surrounding community. An articulated path leads passersby from the street to the composter, inviting them to contribute their organic waste. This gesture not only involves the community in a sustainable practice but also fosters a sense of connection and responsibility toward the centre’s wellbeing.

The composter’s design includes a drainage system: a pipe mounted underneath the drum allows excess liquid, or compost tea, to be siphoned underground into the adjacent vegetable garden beds. This setup ensures that the nutrients from the compost are efficiently utilized, enhancing the health of the garden and symbolizing a direct link between the community’s contributions and the nourishment of the center.

Located near Jena McCarthy’s garden within Gozololo, the composter operates in symbiosis with the garden space. The relationship between the two is clear: the composter processes waste into nutrient-rich compost, which in turn supports the growth of vegetables and plants in the garden. This integration of waste management and gardening creates a closed-loop system of sustainability, where the community’s organic waste becomes a valuable resource for nurturing the garden.

Composter (2004) thus embodies a profound commentary on transformation and regeneration. By converting waste into sustenance, the artwork parallels the reclamation of Gozololo itself from a rubbish site to a place of care and growth. It stands as a testament to the potential for renewal and the inherent value found in what society often discards, transforming decay into a source of vitality and sustenance.

“Suitably wry, a dotted blue plastic compost bin is inserted into the perimeter fence of ‘Gozololo’. The white dots puncture the surface of the bin and thus aerate the collected waste and detritus of the site, processing it into compost. The piece is both conceptually rich as well as literally enriching. Streak’s piece has dots that mark the spot, a spot that sits not on the fence but in it, a funky visual/verbal pun that allows access from both sides – it links both the inside and outside of ‘Gozololo’.” – Virginia Mackenny

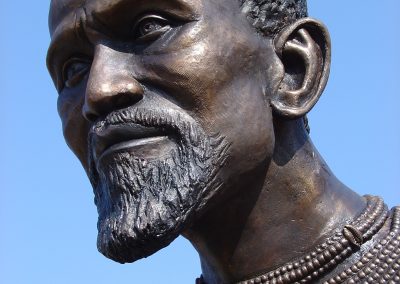

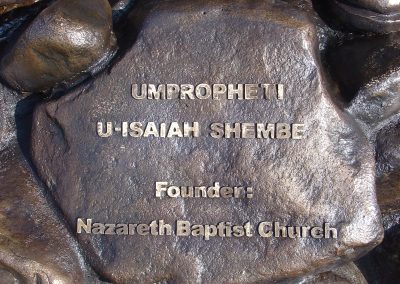

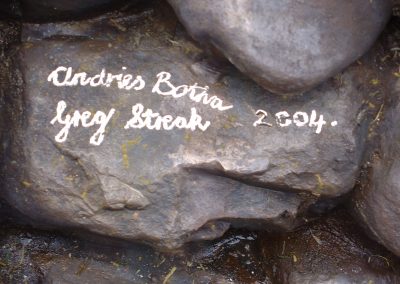

Prophet Isaiah Shembe (2003 / 2004)

Artists: Greg Streak / Andries Botha

Location: South Beach Durban

Work: Prophet Isaiah Shembe (2004)

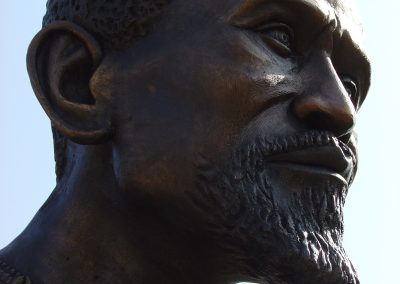

The installation in Durban of the statue of The Prophet Isaiah Mloyiswa Mdliwamafa Shembe is a landmark initiative as it will be the first African statue in the eThekwini Municipality. His energy and spirit has been shown in the winning submission for the commision of the statue by Andries Botha and Greg Streak.

At the project signing ceremony, Head of the Parks, Recreation and Culture department Thembinkosi Ngcobo stated that …”we have finally reached the point where one of the movers and shakers of South African Resistance History will finally be acknowledged for his contribution for not fearing oppression and the mighty wrath of the colonial regime.”

Thembinkosi Ngcobo added that academic writing on the Shembe movement/religion was “more extensive than on any other African-initiated church in South Africa. Scholars have emphasised the historical contribution of Shembe to African society’s spiritual resistance in KZNl during the brutal period from the 1910 Union onward, when Settler legislation resulted in political exclusion of the black middle class, and bitter deprivation for the masses.”

While Isaiah Shembe was the founder of an African Independent Church, the Statue being erected is to honour his entrepreneurial foresight as well as his insistence on retaining Zulu beadwork as part of dress, his political savvy and his courage to confront the repressive regime of the Native Administration.

The Shembe Statue is to be located on the beachfront overlooking the spot where the Prophet is known to have parted the waters.

The sculpture was completed in 2004, but due to faction fighting and accusations of politics around the work, it remains to date wrapped and in storage within one of the Durban City warehouses.

Drain (2002)

Project: Violence / Silence

Curator: Greg Streak / PULSE

Location: Nieu-Bethesda, South Africa (2002)

Work: drain

Entitled simply Drain (2002), the piece is minimal. Streak sunk a drainpipe with steel collar into the middle of the cement floor of an old abandoned reservoir. With the aid of some coal dust the interior of the pipe becomes fathomless, plunging into a deep blackness of unknown depth.

The empty reservoir reads as drained of its life-giving contents. It is both a salute to the harsh environment and the farmers, who battle the elements, as well as a powerful metaphor for psychological space. Whilst to drain is to make dry, discharge and carry waste, it is also to deplete and exhaust. Here, the drain can exist in the very centre of one’s being. Streak notes that it is “a chamber – a cavity in the body of an organism” and hence, it reads as an image of a great emptying.

The disturbing power of Streak’s piece lies in its deadly quietness that succinctly combines the unsettling dialogue of the exhibition theme of Violence/Silence. – Virginia Mackenny

Streak’s Drain (2002) is an arresting and poetic response to the psychological trauma of nothingness. An emblem of emptying, removal, even purging, Streak likens its industrial, impersonal form to “a chamber in the body of an organism”, an orifice in a void whose quiet presence seems rather deadly. – Kathryn Smith

Untitled (97 linosa close) (2001)

Project: Further up in the Air

Curators: Leo Fitzmaurice / Neville Gabie

Location: Liverpool (2001)

Work: untitled (97 linosa close)

Further Up in the Air (2001-2004) was the follow up project to Up in the Air (2000 -2001). Both were two ambitious programmes of artists residencies in Sheil Park, Liverpool, jointly initiated and managed by artists Neville Gabie and Leo Fitzmaurice. The residencies and resulting temporary installations coincided with the redevelopment of the whole Sheil Park site, the demolition of existing 1960s tower blocks and the creation of high quality new homes on the same site.

Eighteen artists took part in Further Up in the Air. Building on the success of the first project, information for artists was produced for Further Up in the Air and a press release garnered even wider interest. Both projects have been well documented and critically received in seminars, conferences and publications. One of the exciting and unusual aspects of the two projects has been the continuing programme of activity they have generated.

Artists and cultural practitioners included Lothar Gotz, Will Self, Elizabeth Wright, Stefan Gec and Paul Rooney

In Further up in the Air, I confronted the uneasy sense of intrusion that accompanied our exploration of countless abandoned apartments in Liverpool. Each apartment was a silent witness to its former occupants’ lives, filled with their personal belongings and traces of their existence. Some of these spaces had remained untouched for over three years, their inhabitants having either passed away or left abruptly. As I navigated through these intimate environments, I felt like an intruder, a voyeur peering into the private realms of others’ lives.

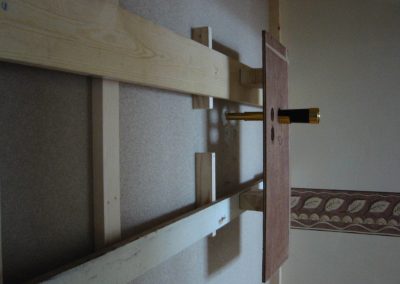

My intervention in Apartment 97 emerged from this tension between curiosity and respect for privacy. I sought to subvert the very experience of intrusion by constructing a barrier that denied access to the apartment’s interior. Upon opening the apartment door, one would immediately encounter a false wall positioned half a meter beyond the entrance. This wall, meticulously crafted and integrated into the existing structure, created a small cubicle entrance space that offered no passage into the apartment itself.

To enhance this space’s disorienting and clinical atmosphere, I sanded the floors, painted the door and the electrical box in glossy white enamel, and wallpapered the walls with a white tread plate pattern. The interior resembled a clean, sterile environment devoid of emotional warmth. The skirting board from the apartment walls continued seamlessly onto the false wall, with a dado rail concealing the division where the lower section could be removed to access the apartment. Centrally placed at eye level in this false wall was what appeared to be a security viewer—a device typically used to peer into the hallway from the apartment.

However, this was not a conventional security viewer but the eyepiece of a telescope mounted behind the wall. In the concealed space of the apartment, I constructed a rudimentary wooden framework to hold the telescope horizontally. Positioned approximately six meters away from the telescope’s end was a peculiar assembly of differently sawn pieces of wood, supporting a 2×1 meter mirror at a 45-degree angle to the telescope’s focus. This setup reflected the image of white wind-driven turbines on the coast, about three miles away. The telescope’s focal lens was adjusted slightly out of focus, secured in place with silicon sealant to ensure a deliberately unclear view.

During the open studio days, when visitors explored the interventions in the tower block, they would inevitably arrive at Apartment 97 with expectations shaped by the other installations they had seen. As they opened the door, they were immediately confronted with the false wall, blocking any further exploration. This abrupt denial of access subverted their voyeuristic tendencies, leaving them facing a wall that blended seamlessly with the surroundings, effectively closing off the apartment’s private spaces.

For those who noticed the security viewer, it offered a second layer of non-delivery. Expecting a glimpse into the apartment’s interior, they instead saw an indirect view of the outside world—an out-of-focus, jittery image of the distant wind turbines. This blurred, moving scene resembled an old silent film, disorienting and elusive, far from the anticipated intimate view of the apartment.

The intervention played on the idea of expectation and denial, challenging the viewer’s assumptions and their inherent curiosity about private spaces. By redirecting their gaze from the apartment’s interior to a distant, unclear vista, Further up in the Air questioned the voyeuristic impulse and the ethics of intrusion. In doing so, it transformed the act of looking into a reflective experience, where the anticipation of insight was met with the reality of obscured vision and unmet expectations. This deliberate frustration of voyeuristic curiosity not only protected the sanctity of the apartment’s private history but also prompted a deeper contemplation of the nature of observation and the boundaries of personal space.

Hermit (2000)

Project: !Xoe Bienale(2000)

Curator: Mark Wilby / Ibis Art Centre

Location: Nieu-Bethesda, Klein Karoo

Work: hermit (2000)

Hermit (2000), is a minimal, beveled, cruciform shape sunk into the earth. Simultaneously archaic yet reminiscent of what we’re told evidence from alien landings might look like, Hermit is a suffocating, invisible tomb – the criss-cross roofs of a house, bastion of domesticity and signifier of culture rather than nature, now subsumed by its harsh environment. Considering Streak’s ongoing project – Proposals for places I’d like to live – there is a sense of irony here. Hermits, in many instances, choose their isolation. It’s a self-imposed imprisonment rather than an enforced one.

– Kathryn Smith